Tips For Winterizing a Garden in Central Texas

Tips For Winterizing a Garden in Central Texas

Temperatures have finally dropped (maybe for good), and there’s one thing on every Texas cultivator’s mind: winterizing the garden.

Whether you’re a homeowner with landscape shrubs, an avid gardener with colorful flower beds, or a farm-to-table vegetable grower using steel planter boxes, you know how important it is to prep your plants for winter.

There’s plenty you can do to help. Winter is a key season in any plant’s growth cycle, and there are benefits available. In fact, most plants will do some of the work themselves.

Check out this list of our favorite tips and tricks to help your plants not only succeed, but thrive through winter in Texas.

1. Water Deeply Before a Freeze

It might be counterintuitive, but watering plants before a freeze actually helps roots stay warm. Soil is a natural insulator — it changes temperature more slowly than air. And wet soil cools even more slowly.

“Water loses its heat slowly over the hours into the colder temperatures,” Texas A&M AgriLife advised. “Watering just before the freeze can help by creating warmth.”

2. Add Mulch or Leaf Litter To Boost Insulation

Have you ever stopped to wonder how even small plants can survive weeks of bitter-cold temperatures? While the above-ground structures of species like woody natives are especially resilient, it’s what happens inside the soil that counts.

The best way to protect that functionality: mulching.

Soil is an excellent insulator. In Texas’ tumultuous climate, that’s a key to any native plant’s survivability.

Consider those weeks when daytime temperatures swing between 40 and 75 degrees. Even in a cold front that lingers for a few days, the soil can retain a lot of ambient heat.

That’s like a jacket for plants.

“During these big swings, soil will typically stay closer to an average temperature,” Opperman said. “Just because air temperature drops, that doesn’t mean the depth where these plants have roots is going to be that cold.”

Maas Verde recommends sprinkling fresh mulch or leaf litter on garden beds ahead of the coldest winter temperatures. The added material will help limit heat loss at the soil surface.

3. Choose the Right Plant Covers for Freezes

With eco-friendly planting practices, gardeners aim to create sustainable gardens that are in harmony with the local environment. However, even the most thoughtful planting cannot fully protect plants from the dangers of freezing temperatures. Freezes can shock plants when the air deposits frost on their leaves and stems, causing their cells to rupture as water inside becomes ice and expands. This can happen anytime the temperature stays low enough to freeze standing water on the ground.

While covering plants with tarps, towels, or blankets will help, it’s not ideal. Breathability, sunlight penetration, and weight are all concerns — using the right tool for the job is important.

For beds, Maas Verde recommends a medium-weight UV fabric like DeWitt’s N-Sulate. It’s purpose-engineered, reusable, and generally easy to handle.

For winterizing potted plants or trees, you can use a Planket. Essentially the same thing in a parachute shape with a drawstring closure, it tightens around plant bases or pots for convenience. Multiple sizes are available.

4. Build Your Own Plant Caddy

The “if you’re cold, they’re cold” feels — we’ve been there, too. And whether or not you’re sentimental about your plants’ comfort, sometimes a plant just needs to come inside. Young individuals with shallow roots can be especially vulnerable to extreme cold, and even bringing them inside the garage can make a difference.

Have you ever noticed how so many plant caddies are the same size and shape? Our resident gardeners know plants are the opposite of that — they come in every size and shape.

For a quick solution, get a plastic bus tub or metal galvanized tub and add casters with construction adhesive or nuts and bolts. This simple design will fit various pot sizes and keep water off your floors.

Or you could hit the same function with a different aesthetic by using a wooden craft crate. For floor protection, consider plastic bin lids or pot saucers.

5. Fertilize in Early Winter

You don’t want to fertilize too late in the season. This is because plants have the best opportunity to capitalize on any nutrient recharge when growing conditions are also ideal.

As I write this in early November, that’s exactly the case.

“Treatment right now is a great idea,” Maas Verde project manager Marc Opperman said. “With plenty of sun, warmth, and regular rain before it gets cold, it’s pretty much the best time to give your garden a boost.”

Maas Verde recommends a light layer of organic compost or granular fertilizer, such as MicroLife Multi-Purpose 6-2-4.

6. Your Plants Are Protecting Themselves!

At first glance, it might not look like much is going on with your outdoor plants in winter. But native and non-native adapted species actually spend this time deepening and developing their root systems.

The plant’s above-ground tissues are experiencing dormancy. Instead of using resources to grow leafy tissue, pollinate, or transpire, it’s sending all that energy underground.

“As roots grow, they tend to channel downward to create structure, and send these hairy rootlets out sideways,” Opperman explained. “It’s a surface area thing, and it’s especially important for nutrient uptake, mycorrhizal connection, and all kinds of good stuff.”

In temperatures of about 40 degrees and above, this is how native plants “winterize” themselves. By spring, they’ll be even better prepared to capitalize and grow.

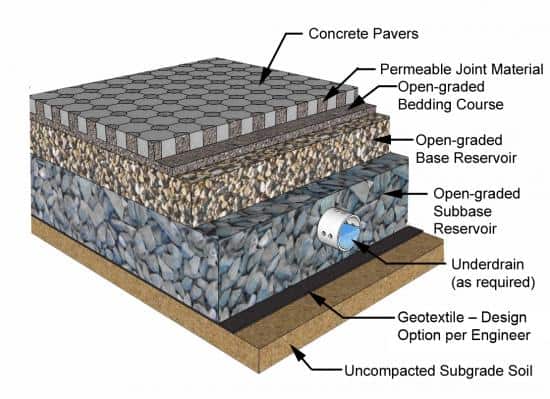

Permeable paver design; (photo/Liangtai Lin via Flickr)

Permeable paver design; (photo/Liangtai Lin via Flickr)